Everyone deserves a fair go

Bigfella Kidman is the first book in an historical fiction saga called The Song of the Butcher Bird, and both the book and the longer story are based on the real life and real character of an Australian Cattle King called Sid Kidman.

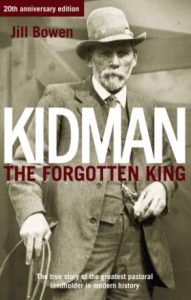

I was working as a jackaroo mustering half-wild cattle in Queensland when I first came across this outback legend, but it wasn’t until about ten years ago that I came across Jill Bowen’s definitive biography of him, Kidman: The Forgotten King. I was working on a memoir of my time jackarooing on Ibis Creek, but when I read Jill’s biography I changed horses and started learning how to write historical fiction instead. Bigfella Kidman is the first result.

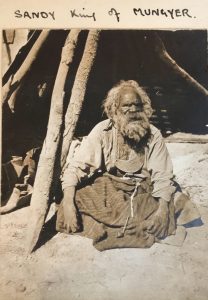

The more I discovered about Sid Kidman, the more fascinated I became by the man and his story, and the more I admired him, not just for his cattle empire-building success but for his love of the outback and horses, his curiosity and decency, and his lifelong belief in the Australian principle that everyone deserves a fair go. In his biography I found out that Sid was one of the few Whitefellas who applied this principle to the Blackfellas. He worked as a teenager with an Aborigine stockman called Billy, and he credited Billy with teaching him most of what he knew about the outback. He employed blackfellas on his stations and insisted they should be treated fairly and with respect by white managers and stockmen.

When he came to England with his family for the first time in 1908, he was shocked by the poverty and hardship of working class life, and he tried to offer a fair go and a new life in Australia to the London horse-bus drivers who were losing their jobs to the newfangled red motorbuses of the London General Omnibus Company.

When he came to England with his family for the first time in 1908, he was shocked by the poverty and hardship of working class life, and he tried to offer a fair go and a new life in Australia to the London horse-bus drivers who were losing their jobs to the newfangled red motorbuses of the London General Omnibus Company.

The Kidmans spent a year visiting their English and Scottish motherlands at an intriguing time when Europe was seething with political and social unrest. Socialism was feeling its way towards revolution in every industrialised country. In Britain and Australia workers were unionising to fight for a fairer go, and women were organising their own political and social unions to claim their right to a voice and a vote in a man’s world.

The fight for a fair go goes on today, but at the beginning of the 20th century when Sid came to London and my story starts, the world was in the early stages of one of history’s most significant upheavals against the old order. Striking unions, socialist firebrands and flour-bombing suffragists were prising open the old patriarchal stranglehold on the world, and we owe them an enormous debt of gratitude for our still much flawed but much fairer society today.

Sid was not a saint or a superhero, but he was a remarkable man in many ways, ahead of his time in his dealings with women and workers, Aborigines and perhaps even the environment, too. The Aborigines knew he would give them a fair go and justice if they were wronged. He was famous for knocking down the price of his cattle or horses at auction for buyers down on their luck, and he inspired legendary loyalty and affection in the managers, drovers and stockmen who worked for him – the best of the outback’s best. When the unthinkable Great War came, he promised the stockmen who joined the fight that their jobs would be waiting for them when it was over, and that he would look after their families while they were serving and if they failed to return. He donated huge amounts to the Australian war effort, and when he died it emerged that for decades he had quietly been doing the same to support charities like the Salvation Army who helped those who needed it most.

Sid was not a saint or a superhero, but he was a remarkable man in many ways, ahead of his time in his dealings with women and workers, Aborigines and perhaps even the environment, too. The Aborigines knew he would give them a fair go and justice if they were wronged. He was famous for knocking down the price of his cattle or horses at auction for buyers down on their luck, and he inspired legendary loyalty and affection in the managers, drovers and stockmen who worked for him – the best of the outback’s best. When the unthinkable Great War came, he promised the stockmen who joined the fight that their jobs would be waiting for them when it was over, and that he would look after their families while they were serving and if they failed to return. He donated huge amounts to the Australian war effort, and when he died it emerged that for decades he had quietly been doing the same to support charities like the Salvation Army who helped those who needed it most.

The Cattle King is the backbone of my story, the golden thread that links its main characters and themes on both sides of the world. He’s the catalyst that propels all my main characters into a new future they could never have imagined before he appeared in their lives: Charlie the young London horse bus driver and Tilly his even younger barmaid wife, grief-stricken for her lost baby; William Saltwood, bitterly resisting his father’s insistence that he should redeem himself and the family property in Australia under Sid’s wing; Rachel Gallagher fighting for Aborigine rights in Queensland, and Mickey, the half-Aborigine boy, picking his way between conflicting worlds.

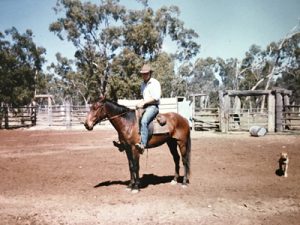

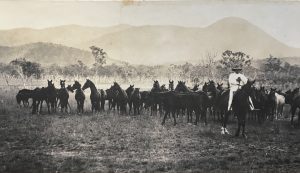

Researching and writing this story brings back vivid memories of that unforgettable year I spent in the Queensland bush. Writing this now, looking north from Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland, I can remember the heat and dust of drought, the huge horizons, the chill of pre-dawn mornings riding out to catch cattle in the open and the thrill of galloping after them as they scattered through the rosewood and gum trees. I can smell eucalyptus, hot horse and saddle leather, and the sharp tang of ammonia in the stockyards. I can hear the call to supper from the house in the sub-tropical darkness, and the invisible chorus of dingoes serenading us from the far side of the house dam. I can remember waking up under the bough shelter in the dawn and hearing the first birds calling in the first light. In my memory it was always the butcher birds who sang first, and their song is the sound of the outback to me, and the soundtrack to my story.

Researching and writing this story brings back vivid memories of that unforgettable year I spent in the Queensland bush. Writing this now, looking north from Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland, I can remember the heat and dust of drought, the huge horizons, the chill of pre-dawn mornings riding out to catch cattle in the open and the thrill of galloping after them as they scattered through the rosewood and gum trees. I can smell eucalyptus, hot horse and saddle leather, and the sharp tang of ammonia in the stockyards. I can hear the call to supper from the house in the sub-tropical darkness, and the invisible chorus of dingoes serenading us from the far side of the house dam. I can remember waking up under the bough shelter in the dawn and hearing the first birds calling in the first light. In my memory it was always the butcher birds who sang first, and their song is the sound of the outback to me, and the soundtrack to my story.

I wish I’d started this story years ago. But perhaps it’s the better for slow cooking, all that practice writing corporate brochures and press releases, and all the experience of life lived mostly in Northumberland and for the past 15 years with Alice and Max and Bea, a dog, a cat and, from time to time, horses, ponies and sheep.

I wish I’d started this story years ago. But perhaps it’s the better for slow cooking, all that practice writing corporate brochures and press releases, and all the experience of life lived mostly in Northumberland and for the past 15 years with Alice and Max and Bea, a dog, a cat and, from time to time, horses, ponies and sheep.

I hope you like the book and want to follow the story. If you do, thank you very much for your interest and support, and please pass the word to your family and friends.

Matt Smalley