The Song of the Butcher Bird | 10 Warrigal

A bite like a crocodile

Rachel had waited all day for the right opportunity to speak to her father, the end-of-the-day moment when he emerged onto the front verandah in the evening lamplight, washed, brushed and ready for his hard-earned dinner.

Jack Gallagher was fifty years old that year, exactly the same age as Sid Kidman, and as strong as a feral bull despite a slight limp inflicted on him ten years previously by a young horse who had violently disagreed with the idea that a man had a right to sit on his back.

As she watched him close the screen door to the house, Rachel felt the rush of affection that always lifted in her whenever she saw that broad, capable, infinitely reliable figure. Her mother had died when she was two years old, and this tough, greying, middle-aged man had been father and mother to her since then. She had also become aware as she grew older that he was one of the most respected station managers, stockmen and horse breeders in the rapidly expanding Kidman empire. As everyone knew, Sid Kidman employed only the best, so her father was the best of the best, and a man she admired as much as she loved him. But there were still some issues on which she thought her father could be improved, and she was not afraid to try.

Jack Gallagher adored his daughter without reservation and she knew it. He was warm putty in her hands when it came to almost any issue that did not involve the fundamental running of the station, and several that did. But on some matters he stood his ground, rocking on his heels, admittedly, and on most of those matters he hoped they could agree not to disagree.

As he turned from the door, Rachel took two steps across the verandah and kissed him on the cheek. They were almost the same height, but he lifted her effortlessly off her feet in a bear hug, whirled her in a half circle and set her down again against the verandah railing. “Stop doing that!” she said with mock ferocity. “Anyone would think I was twelve.”

“You are to me, and always will be,” said her father, grinning at his serious, grown-up little girl. “Anyway, there’s nobody here but us.” He did not include Rachel’s old cattle dog, who had watched this greeting with a jaundiced eye. As soon as Jack let his daughter go, the bitch walked pointedly across to Rachel’s side and lay down heavily as close as she could to her feet.

A gaggle of moths and flying insects were fluttering around the kerosene lamp that hung from the verandah roof, and beyond the lamplight countless cicadas were singing their sand-papery love-songs among the trees. Above the pulsing static of the cicadas they could hear the stationhands eating their dinner in the kitchen, waves of tall talk and raucous laughter washing across the gap between the buildings, and a squawk of delighted outrage from Mella as one of the boys swotted her on the backside as she served them up their steaks, two or three at a time, almost charcoaled, just the way they liked them.

The younger of the two Aboriginal women who worked in the kitchen, Lucy, emerged from the kitchen in a sudden eruption of boisterous noise and carried their own supper around the homestead verandah to their table. In the august presence of the manager, the Aboriginal girl was almost paralysed with shyness, and Rachel moved to the table to help her lay the cutlery, serve the food, and pour a glass of rainwater each for her father and herself.”Thanks, Lucy, she said, “That’s lovely. You can finish now. I’ll clear this away.”

Lucy attempted a jerky cross between a bow and a curtsy to Jack and mumbled something to Rachel so softly that not even the dog’s ears twitched, then hurried away round the corner of the house, her bare feet slapping on the dark rosewood boards. Many of the bigger, stuffier station owners and managers insisted on their Aboriginal house staff wearing shoes, but Rachel was happy to let the women on Warrigal work in the footwear that God – or perhaps Darwin – had given them.

They sat down to eat the same dinner that the stationhands had now finished. Rachel looked across at her father’s plate, piled high with three large steaks, cooked rarer than the men’s, two boiled potatoes and an onion. On a sideplate next to his dinner a miniature mountain of damper bread soaked in beef dripping gave off enough heat to distort the air above it. “Is that going to be enough for you, Dad?” she asked innocently. “The veggie patch isn’t doing too well just now.”

Jack smiled at his daughter. “Perfect,” he said. “You know me. Day like today, I could eat a dead rat on dry toast.” He peered suspiciously at his food. “This isn’t rat again, is it?”

Rachel looked at her father with mild surprise. “Of course it is. Rat today. Roo tomorrow. Goanna on Sunday. Same old menu.” Jack laughed, and they ate without speaking for a minute. In the relative quiet of the cicada serenade and the occasional flare of laughter from the kitchen, the only other noticeable sound came from the old stump-tailed bitch, who was now sitting beside Rachel’s chair, licking herself noisily.

Jack finished his first steak, then abruptly put down his knife and fork. “She does this every time. She knows I damned well can’t stand it.” He glared down at the dog, who stopped for a few seconds, looked up at Rachel, and then resumed her washing.

Rachel put her hand down onto the old dog’s head. “Give it a rest Rosie. Good girl.” The dog gazed up at her, pushing her head harder into Rachel’s hand, and then slumped down onto the verandah planking with a deep groan. “Dad, you’re supposed to have given up swearing, and she can’t help it. She’s a dog. She’s just keeping herself clean.”

Jack gave the reclining dog a look identical to the one she had given him earlier, and picked up his knife and fork again. “It isn’t civilised to have her in the house. You spoil that dog, and she spoils my dinner.” This was a tussle he had first lost the day after he had given his eight-year-old daughter the blue heeler puppy fourteen years earlier, and he had gone on losing it roughly half a dozen times a year thereafter. He cut a chunk off his second steak and rammed it defiantly into his mouth.

“Well,” said his daughter, in a surprisingly conciliatory tone. “Let’s not argue over that.” She paused. “There’s something else I wanted to talk to you about, Dad.”

Jack Gallagher stopped chewing and raised his head sharply like an emu at a waterhole sensing a nearby dingo. “Ah,” he said warily, “I reckoned you might have been cooking something up. Come on then.”

As he spoke, the dog raised her head from the floor, and now she sat up again and looked at Jack, unblinking.

“Right,” he said, putting his cutlery down again. “Is this something I’m not going to like? Are we going to have an argument? Because if we are you can shut that thing in the kitchen first.” He gestured at the bitch with his thumb, and the bitch leaned forward towards him slightly, her eyes locked on his face, her whole body tensing with the message that if he wanted a fight, she was ready to start it. “Look at her!” Jack laughed, taking considerable care not to antagonise the old dog. “The last time we had a minor disagreement she did her best to bite me, and I won’t be bitten on my own verandah. I’m not prepared to talk about anything controversial until she’s somewhere where she can’t take a lump out of me. Besides, two against one isn’t fair.”

“Exactly!” said Rachel emphatically. “That’s exactly what I want to talk to you about, and if you promise you’ll agree with me, I’ll take Rosie across and Mella can keep her in the kitchen, although the men won’t like it.”

“Of course the y won’t like it!” said her father. “They’re petrified of her. She’s bitten every male animal on the damn station at least once, and she’s got a bite like a damn crocodile. And I am not going to promise to agree with you until I’ve heard what you’re going to say.”

y won’t like it!” said her father. “They’re petrified of her. She’s bitten every male animal on the damn station at least once, and she’s got a bite like a damn crocodile. And I am not going to promise to agree with you until I’ve heard what you’re going to say.”

This last proviso followed Rachel’s progress along the verandah, dragging the reluctant cattle-dog awkwardly towards the kitchen, her stump tail clamped tight and her hunched back view a picture of thwarted truculence.

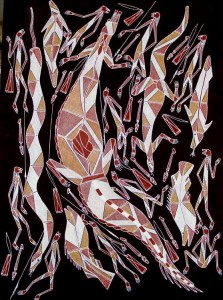

![]() 11. Business, Chiddington Park

11. Business, Chiddington Park